Genital Ulcer Disease

Authors: John S. Czachor, M.D.

Sexually transmitted diseases have been described throughout history. Their impact on personal and public health has been significant, as newer pathogens, some with transmission patterns not exclusively via sexual means, have been identified and added to the pantheon of organisms that bedevil our population. Though not reviewed in this chapter, it is essential to consider Human Papillomavirus (HPV), Hepatitis A, B, and C, and the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) as infections transmitted through sexual contacts. This chapter will focus upon those patients who present with ulcerative genital syndromes, specifically chancroid, genital herpes infection, granuloma inguinale, lymphogranuloma venereum, and syphilis. The approach to the patient with genital symptoms encounters a limited number of pathogens which demonstrate somewhat overlapping clinical scenarios, and may be complicated by the fact that many pathogens are synchronous.

Epidemiology

Chancroid

The causative agent of chancroid is Haemophilus ducreyi, but it was not until the late 19th century that this condition was delineated separately from syphilis. Though modestly common throughout the world, chancroid is infrequently encountered in the United States. As a cause of genital ulcer disease, its rank order is third behind herpes simplex virus and syphilis. Chancroid, by virtue of its isolation difficulties as well as the variable reporting requirements from state to state, is clearly underreported and only 30 case notifications were sent to the CDC in 2004. Selected outbreaks in various urban areas in the United States have been linked to prostitution and illegal drug use. HIV co-infection may exist, and clearly transmission of the infection is enhanced by genital ulceration. Uncircumcised men, lower socioeconomic demographics and patronage with prostitutes pose risk factors for this disorder.

Genital Herpes

The causative agent for genital herpes is the Herpes simplex virus (HSV) of which there are two serotypes: HSV-1 and HSV-2. Both may be pathogenic. HSV-2 is the more common of the two types in genital ulcer disease, although the incidence of primary HSV-1 genital infection may soon approach 50%. Genital herpes is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease in the United States, remains quite prevalent in other North American countries and Europe, but is distinctly uncommon in the developing world. These infections are reported to the CDC as initial visits to physicians for their totals, documenting a steady increase almost annually from 1966 to 2004, as the number of cases has gone from 19,000 to 269,000 in that time frame. Herpes infections are commonly identified amongst most sexually active individuals but have been associated with lower socioeconomic status and men who have sex with men.

Granuloma Inguinale

The causative agent of granuloma inguinale is Klebsiella granulomatis, a Gram negative bacillus formerly known as Calymmatobacterium granulomatis. It is rather rare to find this infection in the developed world unless travel to an endemic area such as the Indian subcontinent, Papua New Guinea, parts of Brazil, central Australia or central and southern Africa is discovered historically. There remains some debate over the exclusive sexual transmission of this disease process, as some extragenital lesion locations clearly suggest a non-venereal route. Donovanosis is so unusual a finding in the United States that any reported information is uncommon and inconsistent. As in the case of other genital ulcer diseases, HIV transmission is enhanced when ulcerative lesions are present.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

The causative agent of lymphogranuloma venereum is Chlamydia trachomatis, serovars L1, L2, and L3. The distribution of this disorder is uncommon in the industrialized world, but may be centered in the tropical areas of developing countries located in Asia, Africa, and South America. Men who have sex with men are the major reservoir for this disease in the United States. There is no national surveillance for lymphogranuloma, although 24 states still report this disease. Only 27 cases were reported to the CDC in 2004. As in the other cases of genital ulcerative diseases, HIV transmission is enhanced in the face of ulcerative lesions.

Syphilis

The causative agent of syphilis is the bacterial spirochete Treponema pallidum. Syphilis has been recognized since the late fifteenth century and has been found all over the world in distribution. The data for syphilis is somewhat difficult to interpret as the information that is reported has combined both primary and secondary stages, thus making an exact evaluation of the number of primary infections open to interpretation. Rates of syphilis have fluctuated greatly over the last 20 years, with an increase seen during the 1980’s, followed by a decline of 90% during the decade 1990-1999. Rates are once again on the upswing in the current decade, and 2004 information revealed 7980 new cases, demonstrating an increase of 11.2% from 2003 totals. Risk factors include HIV disease (both for transmission and reception of syphilis), men who have sex with men, prostitution contacts, lower socioeconomic status, and illicit drug use.

Laboratory Diagnosis

The laboratory diagnosis of genital ulcer disease may be problematic based upon the relative lack, and in some instances, the affordability of diagnostic tests. Combined with the relative insensitivity of those tests which are available, healthcare professionals often make therapeutic decisions centered upon the clinical presentation. However, the clinical diagnosis may not always reflect an accurate appraisal of the situation. Using this measure of diagnosis, various published reports have demonstrated successful treatments ranging from 22% to 82%, depending on the pathogen. Therefore, many organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) endorse therapy based upon syndromic treatment, especially in resource limited situations.

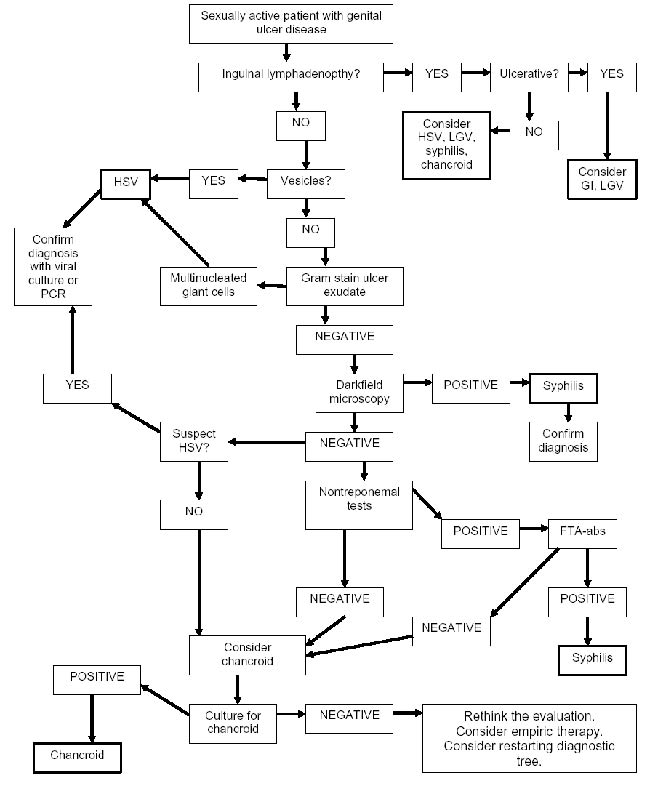

Individuals with genital ulcer disease are usually keenly cognizant of their problem, but on occasion, may be unaware of the affliction. The approach to the patient with genital ulcer disease generally begins with historical information, and encompasses such items as a thorough sexual history, including high risk behaviors such as exposure to partners with known sexually transmitted infections or visible ulcer disease, exchange of sex for drugs or money, use of illicit drugs, same sex contacts, encounters with commercial sex workers, and lack of condom use. A previous history of STD’s is also beneficial information, as is HIV status, if known. A travel history may be particularly important during the evaluation as some ulcerative diseases of the genitalia are not routinely common in the United States. Moreover, having a sex partner from a developing country is essential information as well. A clearly delineated sequence of signs and symptoms related to the infection has to be detailed, including whether the ulcer is solitary or multiple, painful or painless, self-resolving or persistent, and whether or not there is accompanying inguinal lymphadenopathy. A careful examination of the genitalia, perineum and inguinal regions is mandatory. Once these items are completed, then a clinical impression is formulated. This process provides the format from which to proceed (Figure 1). It is important to note that when high suspicion exists for a particular diagnosis, then an option to begin presumptive therapy for that disease should be contemplated while awaiting confirmatory tests.

All patients who present with genital ulcer disease should have a basic laboratory examination for other STD’s, including tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia, with syphilis and HIV serology. Further laboratory examination is based upon the clinical presentation, and which tests are available to the clinician.

Chancroid

Chancroid is usually a diagnosis of exclusion, based upon the historical characteristics and clinical appearance of the ulcerative process. The definitive diagnosis requires the isolation of the causative organism on special media. This media, however, is not routinely available, and if used, only has a sensitivity of approximately 80%. The diagnostic material for culture is best removed from the base of a purulent ulcer, or from the aspiration of a suppurative lymph node, then applied to the special selective media. A Gram stain is not recommended of the material prior to culture, but if done, the classic “school of fish” pattern of gram-negative coccobacilli is seldom seen. No licensed PCR test exists for chancroid. Therefore, the final determination relies on high clinical suspicion with the presence of genital ulceration, and if present, the typical inguinal lymphadenopathy (which may or may not be suppurative), coupled with negative darkfield microscopy and serologic tests for syphilis, and the absence of multinucleated giant cells on ulcer preparation microscopy.

Genital Herpes

There is value in the type specific identification of the species of Herpes simplex that causes genital disease: HSV-1 has fewer recurrences and less subclinical shedding of virus than HSV-2. This is important information when counseling patients with genital herpes. Though not FDA approved for routine use, and not universally available, PCR assays have been employed for species identification. Otherwise, routine viral culture is the standard method for isolating and determining the species of the infecting strain of HSV. Type specific serology might be beneficial to assist with the diagnosis of genital herpes in the patient who has signs and symptoms of infection but negative HSV cultures; or in a patient having a clinical diagnosis without laboratory confirmation; or a patient who has a partner with genital herpes. Screening of the general population for HSV with serology is neither prudent nor practical. Basic microscopy revealing multinucleated giant cells ![]() begins the diagnosis of HSV. Cell culture growth of the virus is the preferred method to confirm the diagnosis, but is not routinely performed. The clinical scenario is relatively distinct, and combined with the microscopy results, the diagnosis is usually solidified. Although not approved for testing of genital specimens, HSV PCR testing is used for spinal fluid analysis for central nervous system HSV infection.

begins the diagnosis of HSV. Cell culture growth of the virus is the preferred method to confirm the diagnosis, but is not routinely performed. The clinical scenario is relatively distinct, and combined with the microscopy results, the diagnosis is usually solidified. Although not approved for testing of genital specimens, HSV PCR testing is used for spinal fluid analysis for central nervous system HSV infection.

Granuloma Inguinale

No culture, serologic, or genetic testing currently exists, thus transforming this diagnosis into one of equal parts high suspicion and exclusion of other entities. The diagnosis is predicated upon the histologic identification of specific findings demonstrated via Wright or Giemsa stains that requires either biopsy or crush preparations of tissue. These findings are known as “Donovan bodies” (hence the name donovanosis) and are actually the micro-organism contained within vacuoles located within macrophages seen on microscopic examination. A negative evaluation for other genital ulcer diseases should precede biopsy of the ulcer.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

The diagnosis is generally based upon clinical suspicion with the exclusion of other more common genital ulcerative diseases such as HSV, syphilis, and chancroid. There is no microscopic examination available to aid in the diagnosis, but cell culture and serology are supportive measures to establish the exact diagnosis. Testing for C trachomatis from clinical specimens via culture, direct immunofluorescence, or nucleic acid amplification tests may be employed if available. Specimens for testing should be obtained from the ulcer base or rectal lesions, although aspiration of lymph nodes may result in higher yields. Genotyping of C. trachomatis to differentiate lymphogranuloma venereum from non-lymphogranuloma venereum serotypes is not widely available. Complement fixation and immunofluorescent antibody serology may enhance the clinical diagnosis. Although these serologic tests may be the most readily available methodology, the delayed reporting renders this a confirmatory test, less useful in the acute setting.

Syphilis

The diagnosis of syphilis requires clinical decision making and diagnostic testing. If an ulcer is present and can be scraped, visualizing the spirochete by darkfield microscopy secures the diagnosis. Serologic testing then confirms the presence of syphilis. Direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) tests of exudates from the chancre may be a useful adjunct if darkfield microscopy is not available. Histologic examination of tissues either using silver stain or immunofluoresence markersmay also be informative. It is immaterial what is seen on the darkfield exam, as nontreponemal testing is ordered for confirmation. Both the rapid plasma regain (RPR) test and the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test are valid tests, with 70%-80% reactivity in primary syphilis. The antibody titers correlate with disease activity, and are used sequentially for monitoring purposes. They will revert to negative after appropriate treatment, although in some instances, these tests may reveal low titer positivity for prolonged time periods, a phenomenon known as the serofast reaction. The results from the RPR and VDRL are not interchangeable, and if done sequentially, they should be performed at the same reference laboratory.

The main objective of the treponemal tests is to confirm a positive nontreponemal serology. The majority of patients in whom the treponemal tests are positive will be so forever, although in some patients (15%-25%), they will revert to negative after several years following successful treatment. The Treponemal pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA, MHA-TP) and the fluorescent antibody absorbed (FTA-abs) test are positive approximately 75% of the time in primary syphilis. One test or the other is used to confirm a positive VDRL or RPR; they are not used to monitor disease activity, and rarely should they be repeated.

If the exudate or ulcer preparation is negative, then the evaluation is centered on the serologic testing for the disease. Once one of the nontreponemal tests (VDRL or RPR) is positive, a treponemal test (FTA-abs or TPHA or MHA-TP) should be positive before the diagnosis of syphilis can be established.

Clinical Manifestations

Chancroid

The incubation period is on average between 5 and 7 days. The initial pustular lesions often erode and become ulcerative. These ulcers may be multiple in numbers, painful, and non-indurated (unless secondarily infected). The most commonly involved sites in men are the glands, corona, or inner surface of the foreskin. For women, most lesions are located at the introitus or labia. Genital lesions may autoinoculate when the ulcer opposes onto the surrounding uninvolved skin or mucosal surfaces. These paired lesions are often referred to as “kissing lesions”. Inguinal lymphadenopathy is bilateral, tender, and found in nearly half of those who are infected with chancroid. The lymph nodes can suppurate and may develop into local buboes if treatment is either delayed or not prescribed.

Genital Herpes

Infection with herpes simplex virus infection is lifelong and recurrent, with time intervals between recurrences as variable as monthly to once per year. Classically, the primary infection is worst in terms of number of lesions and severity of pain. Many genital herpes cases are subclinical, while some individuals may have mild or unrecognized symptoms, and thusly remain undiagnosed. Transmission of the disease occurs with shedding of the virus with active lesions, although despite asymptomatic periods, virus shedding still may occur and transmission proceeds. The incubation period is on average between 2 and 7 days. The lesions are multiple, begin as papules, become vesicles, form pustules, then unroof and ulcerate. A crust over the lesions signals not only the termination of the episode, but the end of the highly transmissible period. Often times the appearance of the papules is heralded by a painful sensation at the affected location, described as a tingling or sun burn-like sensation. Women frequently have erosive cervicitis in addition to the external lesions, while men may have dysuria and urethritis-like complaints in addition to their ulcers. With viremia a component in the pathophysiology of the primary herpes simplex virus infection, nonspecific complaints of fever, malaise, headache and photophobia may be documented. On occasion, neuropathic symptoms such as urinary retention, constipation and pelvic paresthesias are manifest, and are related to the viral involvement of the sacral nerve roots where the infection is centered. Lymphadenopathy, when present, is usually bilateral, firm and tender, but not suppurative.

Granuloma Inguinale

The incubation period ranges from 1 to 4 weeks after exposure, but symptoms may be delayed until 3 to 6 months later. The classic form is a nonpainful, indolent ulcer, sometimes multiple, occasionally destructive, and vascular in nature. The base of the ulcer is often described as “red and beefy”, and bleeds easily. In unusual circumstances, there may be systemic dissemination, often manifested by hepatic and osteolytic lesions. Three other clinical variants are described, including a verruciform or hypertrophic form; a necrotic form with extensive tissue destruction; and a sclerotic form with extensive fibrosis and stricture formation. There is no true lymph node involvement, but pseudobubo formation (granulomatous nodules in the inguinal region encompassing the skin and subcutaneous tissues) is routinely identified. Primary lesions occur solely on the genitals and perineum in 80%-90%. In men, the lesions are commonly found on the glans and prepuce of the penis, while in women, the labia is the most common site. When the fibrotic form of granuloma inguinale is present, it may be complicated by stenosis of the urethral, vaginal, and anal orifices, and genital deformation, including pseudoelephantisasis of the labia.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

The incubation period varies from 3 days to 6 weeks, but routinely averages between 1 and 3 weeks. Of all the ulcerative illnesses, lymphogranuloma venerum is the least likely to present with a genital ulcer. A single lesion is present, usually at the site of inoculation, often self-limited in expression, and may actually present as a papule rather than as an ulcer. The ulceration may be variable in nature, ranging from superficial to deep in depth, sometimes painful, occasionally firm. Many cases are subclinical or go unrecognized. The most common clinical manifestation, however, is enlarged tender unilateral inguinal and/or femoral lymphadenopathy, also know as buboes. When both lymph node chains are involved, they are separated by the inguinal ligament producing the “groove sign”. Although considered pathognomonic for lymphogranuloma venereum, it is found only in the minority of cases. The enlarged lymph nodes are often quite firm and tender, and may spontaneously rupture, forming draining sinuses. Repetitive aspiration may reduce the incidence of rupture and secondary bacterial infection. Proctocolitis and its accompanying symptoms may eventually follow rectal exposure or spread to the perineum via lymphatics from the cervix or vagina in women. Lymphogranuloma venereum is an otherwise invasive, progressive systemic infection, and if not treated early, severe complications are the rule. The genitoanorectal syndrome with its attendant problems are the result of lymphatic obstruction and fistulization, and may be the end stage of a previously unknown lymphogranuloma venereuminfection.

Syphilis

Syphilis has been nicknamed the “Great Imitator” due to its protean manifestations which may mimic various medical disorders. Syphilis is a systemic illness, which if left untreated, will disseminate and manifest multiple phases of disease, each with separate and unique findings. The ulcer seen during the primary stage of infection is called a chancre, and is described as smooth edged, with a nonpurulent base, which may be indurated, but not painful. It is classically solitary. Cell mediated immunity plays an essential role in the host defense’s containment of the organism and the subsequent stages of infection it produces. The genital ulcer at the site of the inoculation is the prominent focus of the infectious process. It will spontaneously heal in 3 to 6 weeks without treatment. Many times the chancre will be inapparent due to its painless nature or because of an inaccessible location or both. It is not uncommon, once the chancre disappears or when symptoms resolve if the lesion is inapparent, for syphilis patients to proceed from the primary to the secondary stage. The net effect is spread throughout the body via the bloodstream, leading to the later stages of syphilis. Regional lymphadenopathy may occur in the primary stage but is more frequent in secondary syphilis. The chancre heals without scarring, although it may become secondarily infected and then have residual abnormalities. Multiple chancres have been documented in approximately 30% of cases. It is important to realize that atypical presentations and disease courses are relatively common. The spirochete also has a propensity to invade the central nervous system during the primary stage, occasionally manifesting as the aseptic meningitis syndrome.

ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY

During the course of some evaluations, there are instances in which no apparent diagnosis can be assigned to the patient with genital ulcer disease. It is at this point when a decision must be made to reinstitute the evaluative process; empirically treat the ulcerative illness while repeating necessary diagnostic testing; or begin empiric treatment for most, if not all, pathogens. Many STD’s have similar epidemiologic links, and it is prudent to consider co-infection at all phases of the investigation.

There is no consensus regarding the empiric therapy of undiagnosed genital ulcer disease. Hperes simplex virus is generally omitted initially, given its distinct clinical course, but many suggest the administration of an antiviral agent following failed bacterial antibiotic treatment. Oftentimes therapeutic options for syphilis remain outside of the recommendations since serologic tests are simple, reliable, and available. The simplest course of therapy would be azithromycin 1 gram orally which will treat chancroid and lymphogranuloma venereum, and begin the first of 3 administrations weekly for granuloma inguinale. An alternative regimen would be doxycycline 100 mg BID for 3 weeks coupled with a single dose ofceftriaxone 250 mg IM, which would cover the most difficult to diagnose genital ulcer disease pathogens as well as syphilis. Occasionally, multiple empiric courses of therapy are prescribed, along with several repetitive investigations without significant improvement. Noninfectious disease processes should be considered if the infectious diseases evaluations remain negative and the patient demonstrates no clinical improvement (Table 1).

Epidemiologic treatments are therapies rendered to those sex partners of diagnosed patients with genital ulcer disease. These “epi-treats” play an integral role in the management of genital ulcers and serve to interrupt future transmission emanating from that newly exposed/infected person, possibly even before signs and symptoms appear in that individual.

Chancroid

Appropriate therapy will cure the infection as well as prevent transmission (Table 2). Clinical symptoms will diminish and eventually disappear over time. Complete resolution of all signs and symptoms is the expected outcome. Patients should notice symptomatic improvement within three days, and certainly by seven days. Larger size of the ulcer(s) may prolong the recovery period. The inguinal adenopathy resolves more slowly than the genital ulcers and may require drainage, which may be repetitive and possibly may include an open surgical intervention rather than needle aspiration. If allowed to remain fluctuant, a suppurative lymph node may spontaneously rupture and convert into a chronic draining sinus. Sexual partners should be treated, whether symptomatic or not. HIV testing is essential. Failure of the infection to resolve might suggest consideration for the correctness of the diagnosis, for the presence of co-infection with another STD, for poor adherence to the prescribed therapy, for resistance to the prescribed therapy, or for underlying HIV infection modifying the disease course.

Genital Herpes

Primary herpes simplex virus infection is treated with antiviral agents (Table 2). Suppressive antiviral therapy following the primary episode reduces the frequency of recurrences by 70%-80%. Acyclovir 400 mg po BID,famciclovir 250 mg po BID, and valacyclovir 500 mg or 1 gm po daily have proven effective. The need for continuous suppression wanes over time, as recurrences often decrease in number and intensity. Treatment choices for recurrent genital herpes include acyclovir 400 mg po TID x 5 days, 800 mg po BID x 5 days, or 800 mg po TID x 2 days; famciclovir 125 mg po BID x 5 days or 1000 mg po BID x 1 day; and valacyclovir 500 mg po BID x 3 days or 1 gm daily x 5 days. On occasion, intravenous acyclovir (5-10 mg/kg IV q 8 hours) may be necessary for those individuals with severe herpes simplex virus disease, for those unable to tolerate enteral therapy, for those with complications resulting in hospitalization (dissemination, pneumonitis, hepatitis), or for those who have central nervous system complications such as meningitis or encephalitis. The intravenous form of acyclovir is continued for 2 to 7 days or until the patient is clinically improved, followed by an oral antiviral agent to complete at least 10 days of treatment.

Sexual partners of individuals with herpes simplex virus genital disease should be evaluated and treated if appropriate. HIV serologic testing should be offered. Rarely, herpes simplex virus infection resistant to traditional first line agents have been isolated. Clinical failure despite appropriate therapy should suggest a search for an alternative diagnosis or consideration of a drug resistant species of herpes simplex virus.

Granuloma Inguinale

The CDC recommends doxycycline for treatment of donovanosis (Table 2). The other alternatives listed have been used successfully around the globe as well. Some experts recommend the addition of gentamicin (1 mg/kg IV q 8 hours) if there is no improvement documented in the beginning of therapy. Treatment is continued for at least three weeks and until all the lesions have completely healed. If there has been little or no improvement following the first two weeks of therapy, then an alternative choice of treatment should be selected. Of note is the fact that once therapy has been given for seven days, Donovan bodies are no longer visible in clinical specimens. Those individuals who have had sexual contact with an index patient having granuloma inguinale within 60 days before the onset of the patient’s symptoms should be examined and offered therapy, even though the value of empiric therapy remains unproven.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

The CDC recommends doxycycline for the treatment of lymphogranuloma venereum (Table 2). Appropriate therapy cures the infection and halts ongoing tissue damage, but regression of the fibrosis and/or scarring previously documented is seldom seen. There is some support for the use of azithromycin 1 gm orally given weekly for 3 weeks, even though there is limited clinical data published. Sex partners who have had contact with lymphogranuloma venereum patients within the 60 days before the onset of the patient’s symptoms should be evaluated for cervical or urethral chlamydia infection, and treated with a standard chlamydia regimen.

Syphilis

Treatment for primary syphilis is penicillin G, administered intramuscularly (Table 2). Other therapy options exist and have been successfully administered in various situations. There is growing evidence for the use of doxycycline in the treatment of early syphilis. Azithromycin has recently fallen out of favor with the failure of therapy for the treatment of early syphilis in men who have sex with men in San Francisco during 2002-2003. An HIV test is part of the evaluation of the patient with syphilis at any stage, and in high incidence areas, it should be repeated in 3 months. Following therapy for primary syphilis, patients should have an evaluation and repeat VDRL/RPR testing at 6 and 12 months. Failure of these nontreponemal tests to demonstrate a four-fold decrease after 6 months indicates either treatment failure or re-infection, and these patients warrant retreatment. However, since re-infection cannot be reliably distinguished from a therapeutic failure (possibly unrecognized CNS infection), CSF examination should be performed. Patients with HIV disease generally require the same dosage of penicillin G, though some experts would recommend a weekly dose for 3 consecutive weeks. HIV infected individuals should be evaluated clinically and serologically for treatment failure at 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24 months.

READING LIST

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Workowski KA, Berman SM. CDC Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2006. MMWR 2006;55(RR-11):1-94. [PubMed]

2. DiCarlo RP, Martin DH. The clinical diagnosis of genital ulcer disease in men. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:292-8. [PubMed]

3. Dillion SM, Cummings M, Rajagopalan S, et al. Prospective analysis of genital ulcer disease in Brooklyn, New York. Clin Infect Dis 1997;24:945-50. [PubMed]

4. Ghanem KG, Erbelding EJ, Cheng WW, Rompalo AM. Doxycycline compared with benzathine penicillin for the treatment of early syphilis. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:e45-9. [PubMed]

5. Hart G. Donovanosis. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:24-32. [PubMed]

6. Mackay IM, Harnett G, Jeoffreys N, et al. Detection and discrimination of Herpes simplex virus, Haemophilus ducreyi, Treponema pallidum, and Calymmatobacterium (Klebsiella) granulomatis from genital ulcers. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:1431-8. [PubMed]

7. Montero JA, Zaulyanov LL, Houston SH, Sinnott JT. Chancroid: An update. Infect in Med 2002;4:174-8.

8. Tramont EC. Syphilis in adults: From Christopher Columbus to Sir Alexander Fleming to AIDS. Clin Infect Dis 1995;21:1361-71.[PubMed]

Tables

Table 1: Differential Diagnosis Of Genital Ulcer Disease

Infectious Causes |

Non-infectious Causes |

|---|---|

Bechet’s disease Erythema multiforme Fixed drug eruption Squamous cell carcinoma Trauma |

Table 2: Treatment of New Onset Genital Ulcer Disease

Condition |

Organism |

Treatment |

|---|---|---|

Chancroid |

Azithromycin 1 gm po once OR Ceftriaxone 250mg IM once OR Ciprofloxacin 500 mg po BID x 3 days OR Erythromycin base 500 mg po TID x 7 days |

|

Genital herpes |

Acyclovir 400 mg po TID x 7-10 days OR Acyclovir 200 mg po 5X per day for 7-10 days OR Famciclovir 250 mg po TID x 3 days OR Valacyclovir 1 gm po BID x 7-10 days |

|

Granuloma inguinale1(donovanosis) |

Doxycycline* 100 mg po BID x 3 weeks OR Azithromycin 1 gm po weekly x 3 weeks OR Ciprofloxacin 750 mg po BID x 3 weeks OR Erythromycin base 500 mg po QID x 3 weeks OR TMP-SMX DS po BID x 3 weeks |

|

Lymphogranuloma venereum |

serovars L1 L2L3 |

Doxycycline* 100 mg po BID x 21days days OR Erythromycin base 500 mg po QID x 21 days |

Syphilis primary stage |

Benzathine PCN G* 2.4 million U IM once daily OR Doxycycline 100 mg po BID x 14 days OR Tetracycline 500 mg po QID x 14 days OR Ceftriaxone 1 gm IM or IV for 8-10 days OR Azithromycin 2 gm po once2 |

*Preferred regimen

1 All regimens are for at least three weeks and until all lesions are completely healed.

2 Less preferred regimen due to recent failures on the United States West Coast.

Figure 1: Approach to the Patient with Genital Ulcer Disease