Diarrhea in Adults

Authors: Juan-Pablo Caeiro, M.D., Herbert L. DuPont, M.D.

Acute diarrhea is one of the most common medical complaints in any population. All practitioners seeing patients with the syndrome should have a working knowledge of: the common causes of illness; when to perform a microbiologic assessment; when to initiate empiric antimicrobial treatment; and when to use symptomatic therapy only. In all patients with acute diarrhea, attention to fluid and salt intake is important.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Global Burden

Acute diarrhea is an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide being responsible for 1.6 to 2.5 million deaths per year in children less than 5 years of age. Diarrhea is the 7th most important cause of death in low-and-middle-income countries after ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, HIV/AIDS, perinatal conditions and chronic obstructive lung disease (15).

A recent survey looking at acute diarrhea in the community in the U.S. demonstrated that approximately 0.72 episodes of acute diarrhea developed per person-year resulting in nearly 200 million cases of illness per year. In the study 41 million individuals with acute diarrhea sought medical attention, 6.6 million persons furnished a stool for testing and 3.6 million were admitted to the hospital. Comparative rates of diarrhea by world region are provided in Table 1.

Definitions and Syndromes in Infectious Diarrhea

Acute diarrhea can be defined as the new onset of passage of three or more unformed stools in a 24-hour time period as passage of an increase number of stools of decreased form compared with the normal state. In either case the duration is less than 14 days. Acute diarrhea is frequently associated with one or more enteric symptoms like nausea, vomiting, increase in abdominal gas, abdominal pain or cramps, tenesmus (intense urge with straining but minimal or no bowel movement), fecal urgency, or passage of stools containing gross blood and mucus (7).

Most cases of acute diarrhea are caused by enteric infection by a viral, bacterial or parasitic pathogen. In Table 2 the important causes of infectious diarrhea are listed.

Categories of Infectious Diarrhea

Secretory Diarrhea

Non-inflammatory, secretory diarrhea usually presents with the passage of voluminous watery stools associated with the presence of abdominal cramps and pain without important levels of fever. The classical cause of secretory diarrhea is Vibrio cholerae O1, the causative agent of cholera, but the syndrome can be caused by nearly any enteropathogen. The osmotic gap, stool versus serum has been used in to differentiate secretory from non-secretory diarrhea. The osmotic gap is determined as follows: Na+ and K+ concentrations found in the stool and multiplying this by 2 with this number subtracted from 290 (the expected plasma osmolality). In secretory diarrhea the osmotic gap is <125, usually <50.

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis is a syndrome characterized by nausea and vomiting with or without watery diarrhea generally caused by ingested viral agents or preformed toxins of Staphylococcus aureus or Bacillus cereus. Clinical criteria have been proposed to differentiate outbreaks of gastroenteritis due to viruses from those due to other causes. Diarrhea due toStaphylococcus spp.,Bacillus cereus and Clostridium perfringens toxins presents with shorter incubation period, typically <10 hours, more vomiting, and shorter duration of illness.

Inflammatory Diarrhea (Colitis and or Proctitis)

Acute inflammatory diarrhea refers to acute diarrhea secondary to an infectious agent infecting the distal gut resulting in mucosal inflammation and inflammatory markers in stools. Typically the patient with colitis passes many small volume stools that may be grossly bloody. In the case of diarrhea/dysentery caused by Campylobacter jejuni and Shigella spp, patients often have fever with temperatures of ≥ 38.5 ºC (101.3ºF). A similar syndrome can be seen in enteric infection caused by Salmonella, invasive E. coli,Aeromonas, non-cholera Vibrio spp or Entamoeba histolytica. Shigatoxin-producing E. coli (STEC) also referred to as enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) cause foodborne outbreaks of inflammatory diarrhea with little or no fever.

A complication of receptive anal intercourse in a gay male is proctitis caused by one of four enteropathogens showing sexual transmission: Neisseria gonorrheae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Herpes simplexor Treponema pallidum.

Persistent Diarrhea

When diarrhea lasts more than 14 days, it is considered to be persistent. The etiologic agents are likely to be different in these cases (8). The most important group of pathogens is the intestinal protozoa, including Giardia, Cryptosporidium and E. histolytica. Other well known parasitic causes of persistent diarrhea are Cyclospora, Isospora and Microsporidium. The bacterial enteropathogens can be implicated in a subset of persistently ill patients. In Table 3 the causes of persistent diarrhea and diagnostic tests are provided. A small percent of patients with protracted diarrhea will be suffering from the poorly defined, Brainerd diarrhea. This illness was first described in 1983 in Brainerd Minnesota. It is characterized by explosive diarrhea that may last for months. The incubation period is about 10 to 30 days and the illness duration approximately 16 months. It has been associated with consumption of milk in outbreak settings. It has been associated with consumption of mild in outbreak settings. Other causes of protracted diarrhea are post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and small bowel overgrowth syndrome from dysmotility of the small bowel. Non-infectious causes of persistent diarrhea include inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), celiac and tropical sprue, and colorectal malignancy. Table 4 shows a suggested initial work up for patients presenting with persistent diarrhea.

Special Settings

Day Care Centers

Infants attending day care centers may be exposed to enteropathogens secondary to environmental contamination when a day care center child develops diarrhea (11). The most common causes of diarrhea outbreaks in day care centers are the low-inoculum pathogens including Shigella, Giardia, Cryptosporidium and Rotavirus. Immunity develops in high-risk day care centers by repeated exposure to prevalent enteric pathogens.

Clostridium Difficile Diarrhea

Clostridium difficile is an emerging pathogen of increasing importance. The important risk factors are underlying comorbidity including advanced age, receipt of antibiotics or proton pump inhibitors. Currently an epidemic of toxinotype III binary toxigenic C. difficile strain is being seen with greater importance throughout the U.S., Canada and Europe (4,19). The disease produced byC. difficileis showing a number of important changes. A high percentage of cases are being admitted to the hospital with the infection. Recurrence rate after treatment is high often in excess of 30% in most studies.

Travelers’ Diarrhea

Travelers’ diarrhea is defined as acute diarrhea acquired by persons during international trips, usually occurring in someone from an industrialized regions during visits to developing tropical and semitropical countries. Travelers’ diarrhea is frequently caused by a bacterial pathogen (9). Poor sanitation of the host country is an important factor associated with enteric disease. The most important vehicle for transmission is food with water and ice being less important.

Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome develops in 3-30% of patients with bacterial diarrhea (14). The severity of initial infection seems to be the most relevant predictor of irritable bowel syndrome. There is a possible role of serotonin, inflammatory cytokines, and mast cells in the PI-IBS. Low-grade chronic mucosal inflammation exists in post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. These changes lead to alteration of small bowel motility and bacterial overgrowth associated with bloating and abdominal discomfort. Most patients with post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome have diarrhea predominant disease and the psychiatric overlay is at a lower frequency than seen in infectious irritable bowel patients without an antecedent enteric infection.

Foodborne or Waterborne Gastroenteritis and Diarrhea

Food is an important vehicle for enteropathogens in all regions of the world. It is estimated that 76 million persons suffer from foodborne diseases each year in the United States (17). The illness leads to 325,000 hospitalizations and 5000 deaths per year. While enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) is the most important etiologic agent in travelers’ diarrhea, the organism occasionally causes foodborne outbreaks in the United States. Enterotoxigenic E. coli has caused extensive outbreaks of diarrhea secondary to contamination of recreational lakes or water parks whereCryptosporidiumis also implicated in outbreak disease. Surveillance data from the CDC demonstrated that 50% of waterborne gastroenteritis outbreaks related to treated water were due toCryptosporidiumand 25% of waterborne outbreaks from freshwater were due to ETEC and 25% were due to noroviruses.

Gastroenteritis in Cruise Ships

The incidence of diarrhea among passengers on international cruises is low but outbreaks of norovirus gastroenteritis are showing outbreaks on a small number of ships. Eradication of Norwalk virus from the affected ships is difficult due to resistance to disinfection and in view of the low inoculum required to produce gastroenteritis.

Diarrhea in the Immunosuppressed Host

Before highly active anti-retroviral therapy, diarrhea was a frequent problem in patients with advanced AIDS. Chronic diarrhea and wasting remain important in the African form of AIDS where anti-retroviral therapy is substandard. Some anti-HIV drugs may cause diarrhea, such as nelfinavir, atovaquone and clindamycin. In advanced untreated AIDS, virtually any enteropathogen can produce diarrhea. Persons with AIDS remain at greater risk of diarrhea than non-AIDS patients.

The most common enteropathogens causing infection leading to diarrhea in patients with AIDS are a group of parasites includingCryptosporidium, Microsporidium, Isospora and Cyclospora. Less common but important causes of diarrhea in patients with AIDS include the bacterial enteropathogens: Campylobacter, Shigella, Salmonella, C. difficile and Mycobacterium avium complex. The major viral pathogens leading to diarrhea in advanced AIDS are HIV which deplete intestinal immunity leading to mucosal atrophy and malnutrition and Cytomegalovirus which causes colitis. The important pathogens leading to diarrhea in HIV/AIDS are listed in Table 5.

Cancer and Organ Transplantation

Patients having undergone solid-organ transplantation (SOT) with immunosuppression experience a high rate of diarrhea. In a study of renal transplant patients with diarrhea of 7 days duration related were found to have enteric infection secondary to Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonellaspp.,Clostridium difficile, noroviruses, CMV, small bowel bacterial overgrowth, and secondary to immunosuppressive drugs including mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and cyclosporine.

It is estimated that 10% to 40% of liver transplant recipients develop diarrheal disease. CMV infection andClostridium difficilediarrhea and colitis are frequent complications. Colitis may appear in the absence of prior antimicrobial therapy.

DIAGNOSIS

Use of the Laboratory in Acute Endemic and Epidemic Diarrhea

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) advocates the performance of laboratory studies of any diarrhea lasting more than a day when associated with fever, passage of bloody stools, or in a patient with systemic illness (13).

We would recommend obtaining stool samples for laboratory studies in patients with diarrhea in the following situations: outbreak settings, in immunocompromised patients, persons with severe disease requiring hospitalization and in travelers with persistent diarrhea.

Fecal Inflammatory Markers

The most sensitive marker of inflammation is fecal lactoferrin, which is a commercially available assay. Finding 4+ lactoferrin in stools is an indication of mucosal inflammation. Numerous fecal leukocytes are found microscopically when a patient has diffuse colonic inflammation characteristically due to one of the following: Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter and C. difficile. Fecal markers of inflammation are not reliable indicators of specific enteric pathogens since they are associated with pathologic process rather than a specific infection.

Stool Cultures

The conventional diagnostic enteric laboratory will routinely identify the presence ofShigella, SalmonellaandCampylobacter. Most labs are able to look for E. coli 0157:H7 if requested to look for this pathogen. The customary way to identifyE. coli0157:H7 is to culture the stool on sorbitol containing MacConkey agar followed by serotyping. Since many Shigatoxin-producingE. colido not belong to the 0157 serotype, complete evaluation for this group of pathogens also involves examination of diarrhea stools for Shigatoxin by EIA.

The laboratory must be alerted to look for Vibrios and employ salt-containing media (TCBS) when this group of bacteria is being sought. The two major indications for culturing forVibriosare presence of shellfish- or seafood-associated dysenteric diarrhea where conventional stools studies are negative or when cholera is suspected based on the finding of profuse diarrhea with profound losses of fluid and dehydration. In the first case, non-choleraVibriosis being sought and in the second V. cholerae is the focus of the study followed by testing for 01 serotype.

C. DifficileToxin Tests and Culture

The diagnosis ofC. difficilediarrhea/colitis is based on finding toxin A or toxin B in stool samples or by culturing the organism from stool. The most sensitive tests appear to be anaerobic culture followed by PCR or cell culture cytotoxicity for toxin B (2). The most widely used test is enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for toxins A and or B.

Parasite Studies

The major indications for parasite tests are when diarrhea is persistent, when diarrhea occurs in an infant attending a DCC, in an adult gay male with diarrhea or when diarrhea complicates immunosuppression. A well trained and experienced laboratory technician is needed for direct microscopic identification of parasites in stools using the trichrome stain. Modified acid fast staining is used for identification of Cryptosporidium, Isospora and Cyclospora. A sensitive and reproducible commercial EIA is available for Giardia, Cryptosporidiumand Entamoeba histolytica. The laboratory needs to be alerted if cryptosporidiosis, cyclosporiasis or isosporiasis are being considered as a modified acid-fast stain is needed to detect the organisms in the stools.

Rotavirus Antigen

Rotavirus is the principal cause of gastroenteritis in an infant 2 years of age or less. There are a number of commercial EIAs available for detection of rotavirus. Each is sensitive and accurate for diagnosis of group A rotaviruses.

Upper Endoscopy, Sigmoidoscopy or Colonoscopy

It may be necessary to endoscopically evaluate for the cause of diarrhea in patients with persistent symptoms and negative stool evaluation for enteropathogens. In the setting of acute diarrhea sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy have a restricted role. They may be appropriated when patient presents with acute and severe inflammatory diarrhea of unclear cause, often to help clarify the presence or absence of C. difficile colitis. Colonoscopy and biopsies have been demonstrated to be useful in patients with diarrhea and HIV infection with CD4 count of less than 100 cells and negative stool culture for enteropathogens (3) and in HIV infected patients with CD4 count of more than 100 with associated weight loss.

EMPIRIC THERAPY

(SEE THE ALGORITHM, FIGURE 1)

ORT/IV Fluids

It is well proven the effect of oral rehydration solution to prevent childhood mortality from diarrhea in developing countries. WHO and UNICEF have approved a new low osmolarity ORS-UNIPAC ($0.05 per generic sachet) for the treatment of dehydration associated with diarrhea in both children and adults.

Reduced-osmolarity ORS has been shown to decrease vomiting, stool output, duration of illness, and the need for unscheduled intravenous fluids compare with standard WHO ORS. There may be an increase risk of transient and asymptomatic hyponatremia in adults with cholera drinking the new formulation. See Table 6 for comparison the old and new formulation.

Oral rehydration solution packets like Ceralyte may be available at stores selling products for outdoor recreation camping or at travel medicine clinics. Pedialyte is available in various forms in most retail stores.

Symptomatic Treatment

Loperamide is a synthetic opiate that exerts its effects on intestinal smooth muscles resulting in retardation of the movement of the luminal column giving more time for fluid and salt absorption. Loperamide has some minimal antisecretory effects. The drug may produce rebound constipation and is contraindicated in persons with inflammatory diarrhea and/orC. difficilediarrhea and colitis due to risk of toxic megacolon.

Loperamide doses are as follow: 4mg orally first dose, then 2mg orally after each loose stool with a maximum of 8 mg per day.

Racecadotril is an enkephalinase inhibitor. Enkephalins are endogenous opioids with pro-absorptive and antisecretory function in the small intestine. Racecadotril has proven to be effective in clinical trials in children and adults (16). While not licensed in U.S. it has been approved in other countries. SP 303 is another antisecretory drug working through an effect of blockade of intestinal chloride channels (5). It is not currently licensed in the U.S. although is available as Normal Stool Formula over the internet. Racecadotril and SP 303 should not produce rebound constipation an advantage over loperamide.

Bismuth subsalicylate (BSS) is an antisecretory agent reducing diarrhea by approximately 40% compared with placebo. While the salicylate is the active antisecretory component in the treatment of acute diarrhea, BSS is an effective preventive in travelers’ diarrhea through the antibacterial effects of the bismuth moiety of the product (10).

ANTIBACTERIAL TREATMENT

A telephone survey in U.S. of diarrheal illness found that 12% of persons with acute diarrhea had received an antimicrobial agent by their physician. This rate closely approximates the frequency of bacterial enteric infection and associated diarrhea in the U.S.

Empiric antibacterial therapy is indicated in patients with fever who are passing gross mucus and blood in stools. A second condition where empiric therapy is indicated is moderate to severe traveler’s diarrhea since bacterial enteropathogens explain most of these cases.

Fluoroquinolones are the most frequently employed antibacterial drugs for infectious diarrhea in adults. In a placebo controlled study ciprofloxacin was shown to be effective in decreasing the duration of diarrhea in patients with severe community acquired diarrhea (defined as 4 or more liquid stools per day for more than 3 days, associated with fever, vomiting or abdominal pain). Norfloxacin, ofloxacin and levofloxacin are other fluoroquinolones that have shown to reduce the duration of diarrhea and other symptoms.

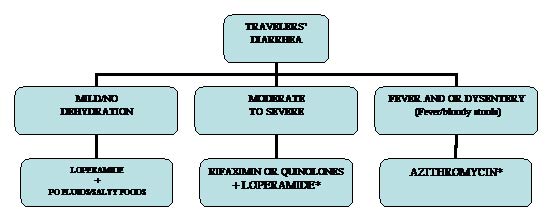

Treatment of travelers’ diarrhea (Figure 2) is best initiated by the affected persons employing self-therapy with antibacterial drugs taken with them on their trip. The three proven drugs in this condition are rifaximin 200 mg TID for three days, or a fluoroquinolone taken daily for three days. Azithromycin in a dose of 500 mg once a day for three days is the preferred treatment for febrile dysentery due to the increasing importance of ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter (Table 2).

Specific Antimicrobial Agents

Rifaximin

Rifaximin is a non-absorbed (<0.4%) rifamycin antimicrobial drug that is effective in reducing diarrhea caused by non-invasive bacterial enteropathogens. The drug is useful in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea where there is an absence of fever or dysentery. The drug has been used as a chemoprophylactic agent in the prevention of travelers’ diarrhea (6).

Azithromycin

Azithromycin is an azalide antibiotic with activity against virtually all enteric bacterial enteropathogens causing diarrhea including ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter and invasive Shigella.

Nitazoxanide

Nitazoxanide is effective and is approved for use in the treatment of giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis. It has activity against Clostridium difficile and has been successfully used in diarrhea and colitis due to the organism (18). It appears to have antiviral action and has shortened the course of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children studied in Egypt (20).

Bile Acid Resin

Bile acid sequestrants are generally not indicated for the treatment of acute diarrhea. They may improve diarrhea in patients who suffer tropical-related diarrhea due to the toxic dinoflagellate Pfiesteria piscida (1) .P. piscidamay be found in the south eastern coast of the U.S. and the Gulf of Mexico. Bile acid malabsorption may cause chronic diarrhea that would benefit by bile acid binding resin therapy.

Therapy of Persistent Diarrhea

While there are effective drugs in bacterial and in parasitic diarrhea, empiric therapy is not recommended with search for an etiologic agent. Nitazoxanide is a broad-spectrum antiparasitic agent with activity against a wide range of parasitic agents and against some non-parasitic pathogens like Clostridium difficile and Rotavirus. If empiric treatment were given to a patient with protracted diarrhea, nitazoxanide would be the preferred agent. However, no placebo-controlled trial has been done in this situation.

The nitazoxanide dose is 500mg tablets taken with food twice a day for 3 days in adults (12).

Complications of Acute Infectious Diarrhea

Acute diarrhea is a self-limited entity the majority of the time. Rarely it can be trigger complications outside the gastrointestinal tract. Table 7 shows the most significant complications of diarrhea.

CONCLUSIONS

Acute diarrhea is common in all populations. The rate of illness in western countries including the U.S. is surprisingly high relating to consumption of contaminated foods or drink. While the rate of illness is higher in developing countries, the more impressive fact relates to the high rate of death among infants living in areas with reduced hygiene and common occurrence of malabsorption. Having a working knowledge of the important causes of acute diarrhea and an approach to work-up and treatment of acute diarrhea is essential in all primary care settings. Febrile dysenteric illness and moderate to severe traveler’s diarrhea is generally treated with empirical antibacterial therapy. Other forms of diarrhea are best managed after making an etiologic diagnosis through stool examination. We offer a flow chart for management based on presenting symptoms.

REFERENCES

1. Balagani R, Wills B, Leikin JB. Cholestyramine improves tropical-related diarrhea. Am J Ther 2006; 13(3): 281-282.[PubMed]

2. Barbut F,Kajzer C, Planas N, Petit JC. Comparison of three enzyme immunoassays, a cytotoxicity assay, and toxigenic culture for diagnosis of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol, 1993;31(4): 963-967.[PubMed]

3. Bini EJ, Cohen J. Diagnostic yield and cost-effectiveness of endoscopy in chronic human immunodeficiency virus-related diarrhea. Gastrointest Endosc, 1998; 48(4): 354-361.[PubMed]

4. Cheng AC, McDonald JR, Thielman NM. Infectious diarrhea in developed and developing countries. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2005;39(9): 757-773.[PubMed]

5. DiCesare D, DuPont HL, Mathewson JJ, Ashley D, Martinez-Sandoval F, Pennington JE, Porter SB. A double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of SP-303 (Provir) in the symptomatic treatment of acute diarrhea among travelers to Jamaica and Mexico. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97(10): 2585-2588[PubMed]

6. DuPont HL,Jiang ZD, Okhuysen PC, Ericsson CD, de la Cabada FJ, Ke S, DuPont MW, Martinez-Sandoval F.A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin to prevent travelers' diarrhea. Ann Intern Med 2005;142(10):805-812.[PubMed]

7. DuPont HL. Guidelines on acute infectious diarrhea in adults. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92(11):1962-1975.[PubMed]

8. DuPont HL, Capsuto EG. Persistent diarrhea in travelers. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22(1):124-128.[PubMed]

9. DuPont HL, Ericsson CD. Prevention and treatment of traveler's diarrhea. N Engl J Med 1993;328(25): 1821-1827.[PubMed]

10. DuPont HL,Ericsson CD, Johnson PC, Bitsura JA, DuPont MW, de la Cabada FJ. Prevention of travelers' diarrhea by the tablet formulation of bismuth subsalicylate. Jama 1987;257(10): 1347-1350.[PubMed]

11. Ekanem EE, DuPont HL, Pickering LK, Selwyn BJ, Hawkins CM. Transmission dynamics of enteric bacteria in day-care centers. Am J Epidemiol 1983;118(4):562-572.[PubMed]

12. Fox LM, Saravolatz LD. Nitazoxanide: a new thiazolide antiparasitic agent. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40(8):1173-80.[PubMed]

13. Guerrant RL,Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, Thielman NM, Slutsker L, Tauxe RV, Hennessy T, Griffin PM, DuPont H, Sack RB, Tarr P, Neill M, Nachamkin I, Reller LB, Osterholm MT, Bennish ML, Pickering LK; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32(3):331-351.[PubMed]

14. Halvorson HA, Schlett CD, Riddle MS. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome--a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101(8):1894-1899; quiz 1942.[PubMed]

15. Lopez AD,Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ.Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2006;367(9524):1747-1757.[PubMed]

16. Matheson AJ, Noble S. Racecadotril. Drugs 2000;59(4):829-835; discussion 836-837.[PubMed]

17. Mead PS,Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C, Griffin PM, Tauxe RV. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 1999;5(5):607-625.[PubMed]

18. Musher DM,Logan N, Hamill RJ, Dupont HL, Lentnek A, Gupta A, Rossignol JF.Nitazoxanide for the treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43(4):421-427.[PubMed]

19. Pepin J,Saheb N, Coulombe MA, Alary ME, Corriveau MP, Authier S, Leblanc M, Rivard G, Bettez M, Primeau V, Nguyen M, Jacob CE, Lanthier L. Emergence of fluoroquinolones as the predominant risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a cohort study during an epidemic in Quebec. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41(9):1254-1260.[PubMed]

20. Rossignol JF,Abu-Zekry M, Hussein A, Santoro MG. Effect of nitazoxanide for treatment of severe rotavirus diarrhoea: randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2006;368(9530):124-129.[PubMed]

Tables

Table 1. Global Importance of Acute Diarrhea, Morbidity and Mortality

Data |

World |

U.S.A. |

U.K. |

|---|---|---|---|

Episodes of diarrhea (Cases per year) |

4 billion |

211 to 375 million |

9.4 million |

Mortality (Persons per year) |

1.6 million |

3,100 |

>300 |

Episodes of diarrhea (per Person per Year) |

3 |

0.99 |

Table 2. Infectious Causes of Acute and Persistent Diarrhea, Known Pathogenicity and Detection in the Routine Diagnostic Laboratory or the Research Laboratory

Etiologic Agent |

Established Agent (EA) vs. Putative Agent (PA) |

Detected by Diagnostic Microbiology Laboratories |

|---|---|---|

Shigella spp |

EA |

Routinely |

Salmonella spp |

EA |

Routinely |

Campylobacter |

EA |

Routinely |

Enterotoxigenic E. coli(ETEC) |

EA |

Only in research laboratories |

Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) |

EA |

Only in research laboratories |

Shigatoxin-producing E. coli (STEC) |

EA |

If requested |

Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) |

EA (shows strain variability in virulence) |

Only in research laboratories |

Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) |

EA |

Only in research laboratories |

Diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC) |

PA |

Only in research laboratories |

Aeromonas spp |

EA (shows strain variability in virulence) |

Routinely if the laboratory is interested in pursuing |

EA (shows strain variability in virulence) |

Routinely if the laboratory is interested in pursuing |

|

Vibrios (non-cholera) and V. choleraeO1 |

EA |

If requested |

Clostridium difficile |

EA |

If requested (toxin is most frequently sought) |

Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis |

PA |

Only in research laboratories |

Giardia |

EA |

If requested |

Cryptosporidum |

EA |

If requested |

E. histolytica |

EA |

If requested |

Rotavirus |

EA |

If requested |

Norwalk virus and other noroviruses |

EA |

Only in research laboratories |

Enteric adenovirus type 40, 41 |

EA |

Only in research laboratories |

Note: *EA pathogens well-proven to cause diarrhea, PA refers to pathogens that may be associated with infectious diarrhea and its symptoms.

Table 3. Causes of Persistent Diarrhea and Diagnostic Tests

Intestinal Protozoa |

Appropriate Stool Test |

|---|---|

Bacterial pathogens |

Clostridium difficile toxin detection |

Celiac sprue |

Serum transglutaminase antibodies + small bowel biopsy |

Tropical sprue |

Stool fat determination + absorption of D-xylose + vitamin B12 |

Brainerd’s diarrhea |

Clinical picture, possible colonic mucosal biopsy |

Whipple’s disease |

Small-bowel biopsy with PAS staining with PCR assay |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

Anti-saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies |

PI-IBS |

Rome II and III criteria |

Small bowel overgrowth syndrome |

Hydrogen breath test |

Malabsorption |

D-xylose test |

Colon cancer |

Colonoscopy and biopsy |

Immunoproliferative small intestine disease |

Colonoscopy and biopsy |

Collagenous colitis |

|

Lymphocytic colitis |

Table 4. Initial Diagnostic Evaluation for Patients with Persistent Diarrhea

1. Comprehensive history and clinical evaluation 2. Complete blood count and manual differential 3. Complete metabolic panel 4. Folate, iron, TIBC, ESR, vitamin B12 level 5. HIV test 6. Antigliadin and anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies 7. Stool examinations: Guaiac and leukocytes; protozoal parasites; Clostridium difficile toxin assay and qualitative fecal fat |

Table 5. Common Causes of Diarrhea in Immunocompromised Patients (Advanced AIDS or Cancer)

Bacteria |

Parasites |

|---|---|

Clostridium difficile |

Microsporidia |

Shigella spp, Salmonella spp |

Cryptosporidium parvum |

Campylobacter spp |

Isospora Belli |

enteroaggregative E. coli |

Cyclospora cayetanensis |

Mycobacterium avium intracellulare |

|

Viruses |

Fungi |

Cytomegalovirus |

|

Table 6. Oral Rehydratin Solutions: Classical WHO Standard versus Reduced Osmolality

Substance |

WHO-standard |

Reduced Osmolality |

|---|---|---|

Sodium (mmol/L) |

90 |

75 |

Glucose (mmol/L) |

111 |

75 |

Potassium (mmol/L) |

20 |

20 |

Chloride (mmol/L) |

80 |

65 |

Citrate (mmol/L) |

10 |

10 |

Osmolarity (mmol/L) |

311 |

245 |

Table 7. Extra-intestinal Complications of Enteric Infection

Pathogen |

Complication |

|---|---|

Campylobacter |

Guillian Barre and Fisher syndromes |

Shigatoxin-producingEscherichia coli |

Hemolytic uremic syndrome |

Bacterial, viral and parasitic pathogens |

Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome, rarely post-infectious inflammatory bowel disease |

Yersinia spp, Shigella flexneri spp, Campylobacterspp |

Reactive arthritis |

Salmonella spp. |

Extra-intestinal infection involving central nervous system, cardiovascular system, lungs, bones, joints, liver and gall bladder, and genitourinary tract |

Figure 1. Therapeutic Approach to the Patient with Acute Diarrhea

Figure 2. Therapeutic Approach to the Patient with Travelers’ Diarrhea

*Able to take oral fluids replace loses with ORS, unable to take oral fluids replace loses with intravenous hydration.

GUIDED MEDLINE SEARCH FOR:

Reviews

Koo HL, Musher DM. Clostridium difficile

Polage CR, et al. Nosocomial Diarrhea: Evaluation and Treatment of Causes Other Than Clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:982-989.

Subramanian A. Diarrhea in Organ Transplant Recipients

Ward SE, Dubberke ER. Clostridium difficile Infection in Solid Organ Transplant Patients

GUIDED MEDLINE SEARCH FOR RECENT REVIEWS

History

Sack, RB. Prophylactic Antimicrobials for Traveler's Diarrhea: An Early History. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41 (Suppl 8):S553-6.

Lim ML, Wallace MR. Infectious diarrhea in history, Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2004 Jun;18(2):261-74.

Nichols BL. The Shwachman Award of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition 2002: acceptance. Dietary management of the malnourished child with chronic diarrhea: both nurture and nature, J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003 Feb;36(2):168-9. No abstract available.

Nilsson P. Oral fluid therapy in children with diarrhea the biggest life-saver seen from a global point of view, Lakartidningen. 1999 Dec 22;96(51-52):5761-2. Swedish. No abstract available.

Nelson AM, Sledzik PS, Mullick FG. The Army Medical Museum/Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and Emerging Infections: from camp fevers and diarrhea during the American Civil War in the 1860's to global molecular epidemiology and pathology in the 1990s, Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996 Feb;120(2):129-33. Review. No abstract available.