The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb and Its Link to Aspergillus

The history of ancient Egypt is deeply embedded with the supernatural and life after death. The mummification process was a means of preserving the bodies of wealthy and prominent Egyptians in order to fulfill their quest to eternity. It was common to provide items of food, clothing, ornaments, statues of their Gods, or anything else that would be of value in the afterlife. Outsiders who broke into the tombs encountered mystical warnings inscribed on the walls. These appeared to be prophetic following the discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. “Death shall come on swift wings to him who disturbs the peace of the king”.

On November 4, 1922, a team of British archaeologists in Egypt lead by Howard Carter discovered a step cut out of rock that was hidden behind debris near the tomb of Ramesses IV. They found fifteen more steps leading to an ancient doorway that was sealed. The doorway was labeled with the name Tutankhamen. Carter quickly sent a telegram to Lord Carnarvon in England, an ill and elderly man of 57, who sponsored the archaeology project. Carnarvon arrived in Egypt three days before the tomb was opened. The tomb was intact, holding three gold coffins and extraordinary treasures. The boy-king Tutankhamen was found in the third coffin. About four months later, Lord Carnarvon died from what seemed to be an infection possibly initiated by an insect bite. By 1929 eleven people associated with the discovery of the tomb had died of early and of “unnatural” causes. The media labeled this turn of events as the “Mummy’s Curse”.

In 1999 a microbe was hypothesized as the cause of these deaths. Gotthard Kramer, a German microbiologist examined forty mummies and identified several species of mold spores in the dark, dry tomb. Kramer hypothesized that when the tomb was first opened, the fresh air could have caused the spores to be blown into the air and infect the archaeologists through their nose, mouth, or eyes. Food offerings that were left in the tombs before they were sealed may have provided the growth environment for the mold. Upon entering, it was speculated that the spores could lead to systemic infection or even death to the infected individuals.

Dr. Hans Merk from the University of Aachen, took dust and rock samples from the tombs and found spores from Aspergillus species including Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus terreus. Dr. Nicola Di Paolo, an Italian physician, identified Aspergillus ochraceus at Egyptian archaeological sites which has been shown to produce mycotoxins. Dr. Ezzeddin Taha, an Egyptian physician, claimed that the health records of many of the exposed workers were compatible with infection from Aspergillus including rash and fever.

The Mummy’s Curse was also invoked for the tomb of King Casimir IV of Poland (1447-1492) in 1973. Of the twelve research scientists who entered the tomb, four died within a few days of entering the tomb and six more died months later. Dr. B. Symk, one of the survivors conducted microbiological examinations on the tomb and found three species of fungus including Aspergillus flavus. He speculated that the deaths might have resulted from exposure to toxins of Aspergillus.

The scenario of Aspergillus causing these deaths seems far-fetched today based on our knowledge of the pathogenicity of invasive Aspergillus infections. The clinical manifestations in the affected individuals were poorly documented and generally nonspecific. No autopsies or pathological evidence exist for Aspergillus invasion of tissue in any of these individuals. Many of the incidents were embellished anecdotes from newspapers in the 1920’s. There is a lively exchange in the correspondence section of the Lancet in 2003 of the dubious attribution to Aspergillus and its spores. A critical assessment by Brian Dunning of the website Skeptoid concluded that the Mummy’s curse is “adventure fiction” from our pop culture.

Reading List

Cox AM. The death of Lord Carnarvon. Lancet 2003;301:1994. [PubMed]

El-Tawil, S. & El-Tawil T. Lord Carnarvon’s death: the curse of aspergillosis?. The Lancet 2003;362:836. [PubMed]

Qualtest, Inc., Is the "King Tut Curse" Caused by Toxins Produced by Microorganisms?. (http://www.qualtestusa.com/KingTutsCurse.html).

Handwerk, B. Egypt's "King Tut Curse" Caused by Tomb Toxins?. (http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2005/05/0506_050506_mummycurse.html).

Roach, C. King Tut’s Curse. (http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/1864789/king_tuts_curse_pg2.html?cat=37).

Lee, K. Howard Carter and the "Curse of the Mummy". (http://www.unmuseum.org/mummy.htm).

Dunning B. www.skeptoid.com/episode4106, June 24, 2008

Pictures

Outside the tomb of King Tut shortly after it was opened in 1922.

Source: Lee, K. Howard Carter and the "Curse of the Mummy". (http://www.unmuseum.org/mummy.htm)

Archaeologist Howard Carter and an assistant examine the coffin of Tutankhamen with little regard for the "curse."

Source: Time Life Pictures/Mansell/Getty Images

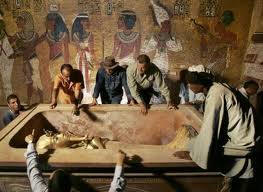

Archaeologists with the mummy of King Tut—Lord Carnarvon was long dead before this event.

Source: Time Life Pictures/Mansell/Getty Images

3,000 year old golden coffin of King Tutankhamen

Source: Gustavo Caballero/Getty Images