Lemierre Syndrome

Authors: Paola Dees, M.D., David M. Berman, D.O., FAAP, FPIDS

Lemierre Syndrome is a rare but important constellation of clinical findings that classically includes four key manifestations: acute tonsillopharyngitis, bacteremia, internal jugular thrombophlebitis, and septic embolization. When first described in the early 1900s, Lemierre Syndrome was almost universally fatal. However, with the advent of antibiotics, mortality rates have decreased from approximately 90% to less than 20%. Once referred to as the ‘forgotten disease’, clinicians must have a heightened sense of awareness to accurately recognize Lemierre Syndrome.

Microbiology

Over 90% of Lemierre Syndrome cases are attributed to Fusobacterium necrophorum. Often difficult to culture, this gram negative microorganism is a strict anaerobe. Other oral flora, Bacteroides and Eikenellagenera, have also been reported as causative organisms in the literature. In addition, gram positive microorganisms such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes have been cultured in cases of Lemierre Syndrome. The incidence of community acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) skin and soft tissue infections has increased exponentially in the past decade, and although not classically associated with Lemierre Syndrome, should also be considered as a potential pathogen.

Epidemiology

Lemierre Syndrome is principally a disease of healthy adolescents and young adults. There is a 2:1 male to female predominance. Incidence rates have been reported to vary between 0.6 and 2.3 per million. There has been a significant increase in the number of documented cases over the past 10 to 20 years.

Clinical Manifestations

As with many common tonsillopharyngeal infections, Lemierre Syndrome typically begins with tonsillitis,pharyngitis, dysphagia, and anterior cervical lymphadenopathy. However, 4 to 8 days following onset of symptoms, the patient progresses to develop persistent spiking fever, rigors, and localized unilateral neck pain and swelling. This second phase of symptoms reflects developing bacteremia and thrombosis of the internal jugular vein. Clinicians will appreciate a discrete area of erythema and induration over, or parallel to, the sternocleidomastoid muscle. In many cases, the patient’s oropharyngeal symptoms may have resolved by the time the patient seeks medical attention for the thrombophlebitis. The late manifestations associated with Lemierre Syndrome result from metastatic abscesses. Lungs are the primary organ affected. Patients may develop putrid breath, productive cough, and chest pain. Cavitary lesions are not uncommon. Large joints such as the shoulders, hips, and knees can also be affected. Presentations can vary from arthralgias to septic arthritisand even osteomyelitis. Infectious complications can also develop within the abdominal cavity. Liver involvement tends to favor female patients, and can manifest as jaundice with hepatomegaly noted on exam. VI and XII palsies have been reported, so any cranial nerve abnormality should alert clinicians to suspect CNS involvement. Metastatic abscesses can also develop in other less common, but nevertheless clinically relevant sites, such as the brain, heart, and soft tissues.

Diagnosis

Lemierre Syndrome is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of the four cardinal features of tonsillopharyngitis, bacteremia, internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis, and metastatic abscesses. Standard throat cultures will typically be negative. If Lemierre Syndrome is suspected, a complete blood count, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, coagulation studies, aerobic and anaerobic blood cultures should be obtained. Anaerobic blood cultures positive for F. necrophorum are not requisite for diagnosis, but should alert clinicians to suspect Lemierre Syndrome if not already part of the differential diagnosis.

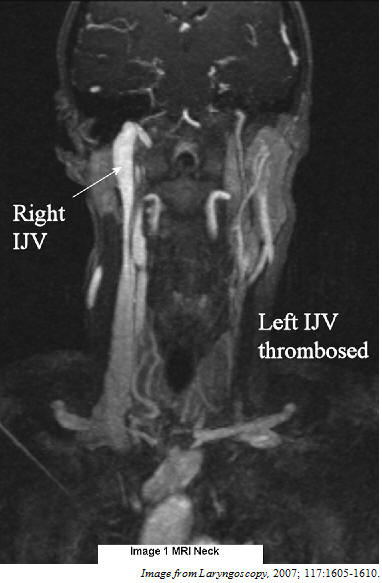

Radiographic imaging of the patient’s neck is paramount. Contrast enhanced CT, MRI, and ultrasound are all reasonable modalities for documenting the presence of venous thrombosis. Each method possesses its own unique advantages and limitations that must be taken into consideration. Ultrasound limits radiation exposure at the expense of limited visualization under bony structures and low sensitivity for an early thrombus. A CT scan offers superior visualization, but has a high radiation burden; and, the need for contrast may be a contraindication in patients with renal disease. Limited access and high cost make an otherwise highly reliable MRI scan less desirable.

The ideal technique to identify metastatic sequelae will be directed by the site of suspected involvement. Plain films may be sufficient to document pulmonary lesions, while an MRI may be superior if osteomyelitis is a concern. Ultrasound and CT can be equally effective for abdominal involvement. In addition, one must consider that repeat or serial imaging may be necessary to document the progression of the jugular thrombosis, as retrograde extension into the cavernous sinus is a rare but dangerous complication of Lemierre Syndrome.

Management

Antibiotics are the cornerstone of treatment for Lemierre Syndrome. Prompt treatment should be initiated as soon as Lemierre Syndrome is suspected. Typical empiric antibiotics include a penicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor,clindamycin, or metronidazole. If a causative organism other than F. necrophorum is isolated, then therapy can be tailored once the susceptibilities are available. Intravenous therapy should be continued for 3 to 6 weeks.

Controversy continues to exist on the role of anti-coagulation as adjunctive therapy in Lemierre Syndrome. Advocates have argued that it may hasten the resolution of an active thrombus and prevent embolic complications. However, opponents cite that the risk of hemorrhagic complications do not justify their usage. Involvement of the cavernous sinus is a factor that points in favor of employing anti-coagulation. Once instituted, therapy should be continued for three months. Close follow-up is important, as with all patients undergoing prolonged anti-coagulation.

References

1. Centor RM. Expand the Pharyngitis Paradigm for Adolescents and Young Adults. Annals of Intermal Medicine. 2009;151:812-5. [PubMed]

2. Fisher RG, Boyce TG. 2005. Moffet’s Pediatric Infectious Diseases: A Problem-Oriented Approach (Fourth Ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

3. Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG. 2008. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (Third Ed.). Churchill Livingstone.

4. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. 2007. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practices of Infectious Diseases (Sixth Ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier.

5. Mohamed BP, Carr L. Neurologic complications in two children with Lemierre Syndrome. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2010; 52, 8:779-781.

6. Syed MI, Baring D, Addidle M, Murray C, Adams C. Lemierre Syndrome: Two Cases and a Review. Laryngoscope. 2007; 117:1605-1610. [PubMed]

Stauffer C, et al. Lemierre syndrome secondary to community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureusinfection associated with cavernous sinus thromboses. J Emerg Med 2013;44:e177-82.

Centor RM. Expand the Pharyngitis Paradigm for Adolescents and Young Adults. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Dec 1;151:812-5.