Fever in the Geriatric Patient

Authors: William A. Woolery D.O. Ph.D. CMD, FACOFP

The original fever of unknown origin (FUO) was defined as a persistent (greater than 3 weeks) body core temperature of 101°F or higher for which no cause could be identified despite a reasonable amount of investigation and the diagnosis remained uncertain after 1 week of study in the hospital. In light of current health management quality review systems a revised criteria for FUO in the elderly has been proposed. These revised criteria require an evaluation of at least 3 days in patient evaluation, 3 outpatient visits for similar complaints or 1 week of logical & intensive outpatient testing without determining the fever cause.

Fever is classified as a temperature increase of 2°F (1.1°C) over baseline which may not exceed 100°F-101°F (37.8°C - 38.3°C). Persistent elevation of body temperature of at least 2°F regardless of the technique of measurement (oral, rectal, axillary, tympanic) has been proposed. Other investigators have suggested an oral temperature of 99°F (37.2°C) or greater on repeated measurement or rectal temperature of 99.5°F (37.5°C) or greater on repeated measurement. Generally older individuals experience difficulty maintaining their body temperature. Their hypothalamus is less responsive to pyrogens and they do not preserve and conserve heat as efficiently as do younger patients.

Despite how you determine fever, a decreased incidence of FUO in the elderly has occurred over the past several decades. This is directly related to increase physician awareness and utilization of advanced laboratory and radiologic studies.

CAUSES OF FUO (Table 1)

Traditionally, FUO has been divided into five categories: infectious, malignant, noninfectious inflammatory disease (NID), miscellaneous and non-diagnosed. The NID category has been classified by other investigators as rheumatic diseases, autoimmune disease, collagen vascular disease and granulomatous disease.

FUO in geriatric patients are related to patient subtypes: classic, nosocomial, neutropenic and HIV associated. Each subtype requires a different process of evaluation although many diagnostic studies overlap for each subtype being investigated.

INFECTIONS

Thirty years ago infections (37%) and multisystem of collagen vascular disease (25%) was the leading cause of geriatric FUO. More recently tuberculosis, especially extra pulmonary sites and abdominal or pelvic abscesses are the most common infections associated with FUO in the elderly. Tuberculosis accounts for approximately 12% of elderly who had FUO. Skilled nursing facility residents are at high risk for this disease. Classic symptoms of hemoptysis, night sweats and a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test response are much less common in the elderly. Weakness, fatigue, unexplained weight loss of 10% of body weight in a short time frame or change in cognitive status maybe the only manifestation of the disease.

Intra-abdominal abscesses account for 4% of geriatric FUO cases. Elderly patients frequently have a prolonged illness with a more subacute course associated with fewer signs and symptoms. This may be related to an altered proprioceptive pain response in elderly patients. Neuropathy and loss of abdominal wall muscle mass and tone may make guarding either impossible or much less apparent.

Osteomyelitis is a rare cause of FUO in the geriatric patient. If this condition does occur, it is almost always monobacterial with the etiologic agent(s) being Staphylococcus aureus or group B- streptococci. Pyogenicvertebral osteomyelitis must be differentiated from extra pulmonary TB spinal osteomyelitis.

Infective endocarditis as a cause of geriatric FUO is infrequent. Most commonly, this disease process occurs in men 60 years or older. Prevalence has increased as a result of the increase number of elderly patients with prosthetic valves, pacemakers, urologic disorders, colon tumors and chronic renal failure. Streptococci and staphylococci account for approximately 80% of infective endocarditis in the elderly. Endocarditis occurs more frequently on the mitral valve. Pacemaker endocarditis is associated with a poor prognosis. Symptoms may be non specific to include lethargy, fatigue, malaise, and unexplained weight loss. The physician must be vigilant in identifying those elderly patients who have multiple risk factors for the development of bacterial infectious endocarditis. The increased frequency of endoscopic procedures in this patient population may necessitate the utilization of appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis.

Viral diseases as a cause of geriatric FUO are rare. Even though cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein - Barr virus (EBV) infections are typical diseases of children, adolescence, and young adults, they can occur in elderly patients. HIV infection occurs in elder adults who have the same risk factors as young adults. HIVinfections in the elderly present with the same opportunistic infections as in younger individuals. Disseminated Mycobacterium avium infection, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, disseminated histoplasmosis and generalized CMV infection are the causes of FUO frequently reported in elderly individuals.

Hepatitis C (HCV) is occurring with increasing frequency in elderly patients. Most of these cases appear to be from latent infections obtained through contaminated blood products 20 to 30 years prior. Castelman disease caused by herpes virus 8 is likely to be reclassified to this group. All elderly FUO patients must be screened for CMV, EBV, HIV, and HCV.

NON INFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

Non infectious inflammatory disease (NID) applies to such diseases as Temporal Arteritis (TA), Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR), Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), Wagner’s disease, Polyartheritis Nodosa (PAN), Crohn’s disease, granulomatous hepatitis, and deQuervain’s thyroiditis.

TA and PMR represent about 60% of cases in this category. PMR and TA are closely related and some investigators consider them to be different phases of the same disease. Seventeen percent of geriatric FUO are caused by TA. The disease is almost always confined to Caucasians; approximately 77% occur in women and peaks in the 7th decade. The incidence is higher in Scandinavia and Northern Europe.

The American College of Rheumatology parameters for the diagnosis of TA include:

1. Age of onset greater than 50 years old.

2. New – localized headache.

3. Temporal artery tenderness or decreased pulse pressure.

4. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) greater than or equal to 50mm/hr.

5. Abnormal temporal artery biopsy.

Symptoms may include fatigue, fever, headache, anorexia, night sweats, weight loss, depression, and unilateral intermittent loss of vision. Typically elderly patients with TA have an ESR of greater than 78 mm/hr and an associated mild normochromic anemia. Intermittent, unilateral vision loss in an elderly patient is TA until proven otherwise.

PMR involves peripheral large joints and is associated with morning and early evening stiffness. A markedly elevated ESR is common but up to 25% of these patients have normal or slightly elevated ESRs.

TUMORS

Lymphoma is the most common neoplastic cause of geriatric FUO (57% of cases). Renal cell carcinoma, atrial myxoma, hepatoma, and colon carcinoma (17%) make up the majority of the remaining cases.

Multiple myoloma is a rare cause of FUO in the elderly (< than 0.2%). However, multiple myeloma should be included in the differential diagnosis of FUO in the elderly.

MISCELLANEOUS GROUP

Pulmonary embolism accounts for 4% of FUO in the elderly. These individuals may not present with classic signs and symptoms of dyspenea, chest pain, or symptoms of pneumonia or heart failure.

Hyperthyroidism, sub acute thyroiditis with thyrotoxicosis is the most common endocrinologic cause of FUO in the elderly. These individuals frequently lack the most striking characteristics of hyperthyroidism. These conditions should be considered in those elderly individuals who have FUO, elevated ESR, and elevated alkaline phosphatase levels.

In the miscellaneous group drug fever is one of the most important causes. Typically, drug fever occurs five to ten days after initiation of the drug, but may occur after the first dose. Fever usually resolves within 48 hours of medication discontinuation. Antibiotics are the most common cause of drug fever in the elderly. Cardiovascular medications, NSAIDS including salicylates, and H2 blockers, anti-convulsants and psychotropic drugs are also common causes. Drug fever can be caused by the route of administration, inherent pharmacologic action and/or direct alteration of thermoregulation or idiosyncratic reaction to a heritable biochemical defect (G6PD deficiency) or hypersensitivity to the drug. Drug fever frequently has no characteristic pattern. Rash, eosinophilia and relative bradycardia are uncommon findings.

In those patients with suspected drug fever a rechallenge and subsequent temperature spike helps confirm the diagnosis. Rechallenge is not recommended in those geriatric patients with underlying cardiovascular disease.

Factitious fever and habitual hyperthermia are not causes of FUO in the elderly.

DIAGNOSIS

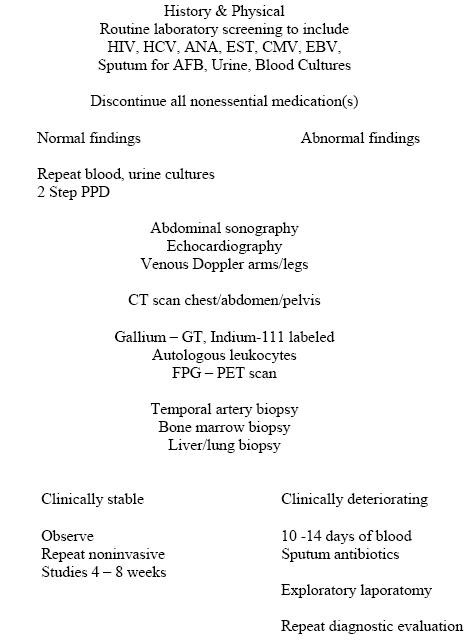

Before undertaking a diagnostic evaluation of geriatric FUO it is important to consider the patient’s overall health. It may be more important to maintain a patient’s quality of life than to initiate the process of identifying and treating a persistent fever (Figure 1).

A detailed history and physical focusing on possible identifying signs and symptoms is self evident. Generally routine laboratory and X-rays are nonspecific. Repeated urine and blood cultures are mandatory. Blood cultures positive for Streptococcus bovis should lead to an aggressive search for Aden carcinoma of the colon. DNA probes are very useful for identifying Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), Mycobacterium tuberculosisand Mycobacterium kansasii.

The presence of coexisting valvular heart disease in many geriatric patients makes it impractical to rely solely on auscultatory findings alone when looking for endocarditis. Transesophagal echocardiography has increased the diagnostic yield of infective endocarditis by 45%.

Abdominal sonography maybe the first choice technique in the diagnostic regimen of geriatric FUO. It is low cost but may yield a wealth of information. Chest/Abdominal CT scan may be the most reliable next step. These scans have a high diagnostic value in detecting two of the most common causes of FUO: intra-abdominal abscesses and lymphoproliferative disorders. A spiral or helical CT scan of the chest with IV contrast is sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in the elderly.

Total body inflammation tracer scintigraphy is a valuable tool in diagnosing FUO. Gallium-67 citrate, labeled leucocytes (Indium-111, technetium- 99), labeled polyclonal human immunoglobulins are most commonly utilized. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) usefulness in the diagnosis of geriatric FUO remains undetermined.

Geriatric FUO patients older than 60 years who have a normochromic normosytic mild anemia, elevated ESR, and an elevated alkaline phosphatase level should generate a high index of suspicion for TA. TA biopsies are positive in only 60 to 80% of patients.

If tuberculosis is considered a two step tuberculin skin test or Quantiferon assay is recommended for those patients who have not been skin tested for many years.

Colonoscopy, bone marrow examination and liver biopsy would be the next steps to consider in the diagnosis workup of geriatric FUO. Bone marrow cultures are not recommended because of the low diagnostic yield.

Exploratory laparotomy is reserved as the final diagnostic measure. It is most helpful when signs and symptoms point to an abdominal source.

If patients are clinically stable it is preferable to observe in an ambulatory setting and repeat non invasive diagnostic studies at a later date. In those elderly patients who are deteriorating a trial of 10 to 14 days of broad spectrum antibiotics are recommended.

SUMMARY

NID’s have emerged as the most frequent cause of geriatric FUOs. TA is the most frequent specific diagnosis. Geriatric FUO is often associated with a treatable condition. Early recognition and rapid initiation of appropriate empiric therapy in those patients who are deteriorating are the cornerstones of a defined management strategy.

Every geriatric patient with FUO requires an individual approach that requires an artistic blend of sound clinical judgment.

SUGGESTED READING

1. Norman DC, Yoshikawa TT. Fever in the elderly. Infect Dis Clin North Amer 1996;10(1):93-99. [PubMed]

2. Mourad V, Palda V, Detsky AS. A comprehensive evidence-based approach to fever of unknown origin. Arch Intern Med 2003;165(5):545-51. [PubMed]

3. Norman DC. Fever in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31(1):148-51. [PubMed]

4. Tal S, Guller V, Gurevich A. Fever of unknown origin in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 2007; 23:649-668.[PubMed]

Tables

Table 1. Common Causes of FUO [Download PDF]

Causes |

|

|---|---|

| Infectious |

|

| Noninfectious inflammatory diseases |

|

| Tumors |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

Figure 1. Diagnostic Algorithm for Geriatric FUO [Download PDF]

What's New

High KP et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation of Fever and Infection in Older Adult Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities: 2008 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Jan 15;48(2):149-71.